“I Recovered. Why Does Today’s Public Health Ideology Pretend People Like Me Don’t Exist?” By Dr. Larry Smith

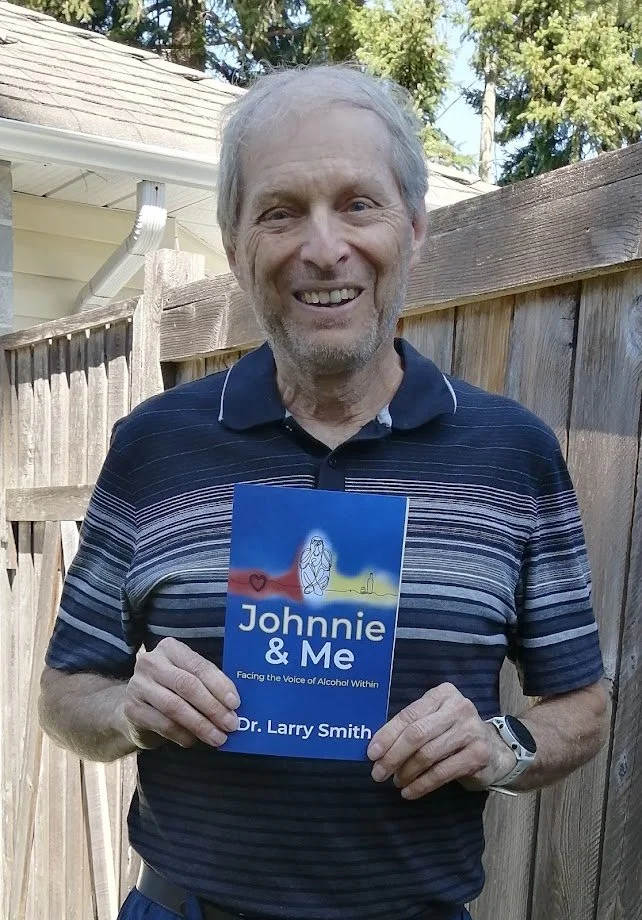

Dr. Larry Smith, author of Johnnie and Me, whose writing explores recovery and hope.

I watched CBC’s recent Fifth Estate documentary, The War on Safe Drugs, with a familiar feeling: the quiet realization that people like me simply don’t appear in today’s public-health storyline. Not because abstinence-based recovery doesn’t exist, but because it doesn’t fit neatly into the current frame. If a form of recovery can’t be easily measured, graphed, or tied to a medical intervention, it tends to fade into the margins—treated as anecdotal rather than essential.

A moment in the documentary captured this dynamic perfectly. A woman was celebrated for being “four years clean.” But in context, “clean” meant four years without street drugs, while still taking government-issued opioids every day. That was held up as the model of success. Meanwhile, recovery without any substances at all—something thousands of Canadians have achieved—never entered the conversation.

It wasn’t questioned. It wasn’t compared. It wasn’t even acknowledged as a possibility.

This narrowing of what counts as “recovery” shows up in other omissions as well. Recently, an abstinence-based recovery fellowship held a major convention in Vancouver, filling one of the city’s largest sports arenas. Local news covered it briefly, but the scale of the event—thousands of people in long-term recovery, gathered in one place—never made it into the national discussion. And it was nowhere in The Fifth Estate’s framing of what recovery looks like in Canada today.

That absence matters. When the largest abstinence-based gathering in the country barely registers, it suggests that the story being told about addiction isn’t being shaped by the full range of evidence. Instead, it is being shaped by what is easy to measure.

This mindset surfaced again in the documentary when two people said they “couldn’t do treatment.” That was the end of the inquiry. There was no curiosity about why. No mention of the many who have done treatment successfully, including those who recovered from opioids without long-term medication. Their stories don’t fit the familiar narrative, so they’re quietly set aside.

This is where today’s public-health framing becomes most revealing.

In our data-driven model, abstinence-based recovery often receives less attention—not because it fails, but because it can’t be quantified the way medication outcomes can. Public-health officials routinely say they “value lived experience,” but only the kinds of experiences that fit neatly into measurable frameworks. And when pressed, they add that there is “a big difference” between alcohol recovery and opioid recovery, as though this distinction automatically invalidates abstinence-based success.

But that claim isn’t anchored in evidence. It’s simply a convenient way to avoid examining the thousands who have recovered fully from opioid addiction without long-term medication. The truth is that many of us exist; we just don’t fit into the columns of a spreadsheet.

This isn’t a debate about whether harm reduction has value. It does. It saves lives. But saving a life is not the same as restoring one. And when public discourse treats chemical stabilization as the full definition of recovery, the human possibilities beyond it disappear.

My memoir, Johnnie and Me, tells the story of my own recovery—messy, painful, spiritual, and ultimately transformative. None of the key turning points in that journey can be captured by metrics. You cannot quantify willingness. You cannot graph surrender. You cannot run a regression analysis on grace. But you can experience it, and it can change your life.

My upcoming novel, 2084: The Neuroxone Conspiracy (now moving through production for a 2026 release), imagines what happens when a society leans too far into the idea that only measurable, medication-based outcomes matter. In that fictional world, recovery is reduced to chemical compliance. Abstinence isn’t just ignored—it’s pathologized. Human transformation becomes an inconvenience rather than a possibility.

It is fiction, yes. But it is informed by a real trend: whenever a system narrows its definition of recovery to what can be counted, it inevitably narrows its definition of humanity as well.

Canada does not need to choose between harm reduction and abstinence. Both save lives. Both help people. Both deserve space. But only one of these pathways is routinely sidelined in public discourse—and it just happens to be the one with no pharmaceutical sponsor and no tidy metrics.

I am one voice. But I am also one of thousands whose stories contradict the belief that abstinence-based recovery is unrealistic or unattainable. You won’t see us much on national television. You may not hear about us in public-health briefings. But we exist. We matter. And our stories belong in the national conversation.

Not because abstinence is right for everyone, but because recovery is bigger than the ideology currently shaping it.

And no matter how inconvenient, that truth shouldn’t be erased.

If these stories resonate, you’re invited to join my Reader’s Circle for reflections, behind-the-scenes insights, and the full Pill and The Promise series in print.

You can sign up anytime at drlarrysmithauthor.com.